Welcome to Issue #1 of Tilting West. The good news is that the new name and approach we announced last week met with a positive response. “You’ve got a great hook with this concept,” wrote Bob Newlon, a subscriber in Malibu. “I’d choose it to read over other articles. Looking forward to seeing what you come up with.”

The comments of Bob and others set me to thinking—and ultimately led me to take an emotional risk and dig into an incident from my basketball-playing boyhood that has haunted me all my life. It is, as I say above, a tale of joy, heartbreak, and healing.

The setting is Hayward, California, where I grew up. Hayward is a mid-sized city south of Berkeley and Oakland and across the bay from San Francisco and Silicon Valley on the Peninsula. So much has changed since the years when I lived there that the Hayward I write about may not even exist anymore. It seems almost imaginary. But I can assure you that my screw-up in front of 10,000 people at the Oakland Coliseum Arena was very, very real. And so was the aftermath. And so are my feelings about it to this day. Please enjoy—Kevin

1. Driveway Dreams

My basketball road to heartbreak began with love—love of the game, which was formed on the driveway of our pink and white two-story house on Minnie Street. My dad bought the rim, strung the netting, and screwed the rim plate onto the facing of the house above the garage. No backboard, just my hoop of dreams fastened directly into the wood. This rectangular slab of concrete with its makeshift hoop served as my Pauley Pavilion or Boston Garden.

What I did there was shoot, shoot, shoot. Dribble and shoot, dribble and shoot, dribble and shoot, shoot, shoot. The touch and feel of my Wilson ball got rubbed out from steady use. The same for the net. Over time its strings frayed from being outside year-round in the summer heat and winter rains. One by one each of the strands that connected with the rim broke off and fell away, leaving nothing but a naked orange hoop. Who needs a net anyway? I kept shooting.

I played after my day was done at East Avenue Elementary, and I resumed my driveway games after dinner at night with the dim yellowish globe of our front door light on. If the ball clanged too hard against the rim or if it hit the house at a wrong angle and I couldn’t catch it in time, it would carom into the street or across our front lawn and start rolling. Our house was in a tract neighborhood in the hills. The Croghans lived across the street from us. On either side of them were the Camerons and the Halls. Next to us on the downhill side were the Grahams. Everybody pretty much knew everybody else in the neighborhood.

Once that old Wilson reached the street it would shoot past the Grahams rolling in the gutter knocking against the curb and heading fast downhill. The race was on. I would take off trying to catch it before it rolled all the way down to Bland Street where we staged our neighborhood touch football games in front of the Kulis house.

While keeping an eye out for cars coming down the street I’d scoop up the ball, bring it back, and start shooting again. That’s about all there is to that story. Generally speaking, there wasn’t a whole lot of excitement in our neighborhood.

Eventually the rim met the same fate as the net. The screws holding the metal plate onto the facing of the house loosened with all the pounding they were taking and gradually pulled away. We had to take it down. What was left was nothing but a discolored rust-stained square and the four torn screw holes. I didn’t care. Who needs a rim? I kept firing away as if the hoop and net were still there. A made basket in my imaginary games between the Lakers and the Celtics was when a jumper hit the screw holes on the square.

Some warm summer nights Rod Mendelsohn, a kid from the neighborhood, would come by and watch me in action. “You do know there’s no hoop there, right?” he’d say. It was a standard joke with us. We’d laugh and shoot the shit and pass the time away.

Mostly I played alone. Sometimes Rod or another kid would step in and we’d battle it out one-on-one, both chasing after the ball when it tried to make its escape to freedom. My first organized basketball games did not occur until Bret Harte Junior High when I played on the seventh and eighth grade teams. Our games were against other junior highs (middle schools) in an area-wide schoolboy league. They were a fairly dismal display, sort of like middle school in general. The scores were 23 to 18, or something crazy like that. The ball was too heavy and the ten-foot high rim was too far up in the stratosphere for anyone that age to make baskets with any degree of accuracy. Mostly we skidded up and down the court in our sneakers missing shots.

Eighth grade was a mess for me anyhow. That was the year my dad died. I retreated into a kind of personal shell. Aspects of my life that were important before that fell apart like my old rim and netting. Gratefully, though, I said goodbye to Bret Harte and entered Hayward High as a 14-year-old freshman. My brother was a senior at HHS and he could keep an eye out for me, reassuring our mother. My body was maturing. I felt stronger. The ball was not as heavy as it used to be and the height of the hoop wasn’t as intimidating. I tried out for the frosh-soph basketball team and made it, and at least in a sporting sense my life began to brighten.

2. Number 12

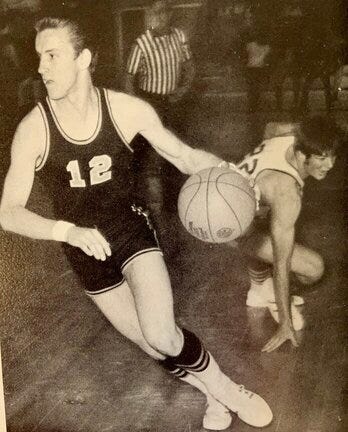

One reason I felt better was a guy I started playing with, another freshman on the team, Donnie Schroer. He came from a different middle school in another part of town. In superficial ways we didn’t have much in common. I lived in the hills, he lived in the flats. My wavy blond hair was long and shaggy; he used product in his hair and smoothed it back in a style favored by the guys in his part of town. His upper body was stronger and more solid than my lean skinny-boy frame. I had him by two inches in height—I was 6-foot-1—but Number 12 absolutely crushed me in another important basketball measurement: vertical leap.

“That white boy could jump,” said Manny Silva, a talented shot-making guard who played against Donnie and me when Sunset High faced Hayward High in Hayward Area Athletic League competition. While doing research for this story I called Manny up to get his take on Donnie as a player, and he was more than happy to talk about his old friend. Not only could Schroer get up off the floor, he knew what to do once he was up there. He possessed that rare, even mystical quality that some jumpers have where they can hang ever so slightly, for a split second, as if suspended in mid-air by invisible strings. His ability to soar enabled him to perform dazzling acrobatic moves as his more earthbound opponents and teammates (such as myself) stood by watching in admiration.

Also as part of my research, I pulled out a scrapbook of newspaper clippings compiled by the wife of our coach, Joe Fuccy, during our senior season. Joe gave me the scrapbook some years ago but I had never looked at it much, largely because of the painful memories it stirred up for me. I overcame my qualms though and found a quote from Donnie talking to a newspaper reporter about his style of ball.

“What I really enjoy,” he said, “is getting caught up in the air when you’re intending to pass off. Somehow you’re forced to make a wild shot of some sort and with luck it goes in.” This is false modesty on his part. I saw enough of those wild shots go in to know it had nothing to do with luck.

On a basketball court Donnie’s style and mine fit together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. On his twisting, hang-time displays if he did not see an opening he’d kick the ball out to me on the perimeter. All those hours in the driveway had made me a decent threat from the outside, a long-range shooter the opposing team had to respect. We made for a pretty dynamic pair in our frosh-soph years, and when we turned 16 and automobiles became an every day fact of our teen lives we started having fun off the court, too.

Donnie drove a pumped-up silver Volkswagen Beetle that made for a good getaway car for whenever he was in the mood to pursue his education not in school but on the streets. I joined him on several of his getaways. So did Silva, a retired police officer who spent 30 years on the force. “I’d be in class and I’d hear somebody whispering at me from outside and I’d look over and there’d be Donnie, peeking his face over the edge of the window frame gesturing for me to come outside. I’m thinking, ‘Doesn’t this guy ever go to class?’”

Our main jam was at Quarter Pounder on Mission Boulevard next to the Hayward Plunge. Open 24 hours, it never closed, not even for Christmas or New Year’s. It was a gritty little greasy spoon diner that bore no resemblance to the one in Happy Days. You sat at a counter facing the grill with your back to the picture window that looked out on all the traffic roaring by on Mission. Behind the counter were two guys in stained white aprons. They grilled the burgers, deep-fried the sliced potatoes in boiling vats of murky oil, made the milk shakes that were served in silver canisters. Every Quarter Pounder hamburger came on buns slathered with a secret sauce that resembled Thousand Island dressing.

We ate there for lunch during school hours, after practice, and after a night of aimless joy-riding on Mission and East 14th Street. On Friday and Saturday nights its parking lot was always jammed with hopped-up vehicles and guys who wore their hair smooth and slick the way Donnie did. It did not matter what time of day or night it was, Donnie knew every employee on a first name basis, and every employee returned the compliment.

The guys behind the grill would always want to hear about Donnie’s latest exploits—his obsessive relationship with his on-again, off-again girlfriend Debbie, or his gambling adventures at Bay Meadows Race Track across the bridge in San Mateo. Even in high school Donnie regularly went to the track, loved to play the ponies, loved to gamble. I went to Bay Meadows with him a few times. We snuck in. So did Manny and his other pals. In retrospect maybe we should have been less carefree about gambling, but we were young and it all seemed like harmless fun at the time. Besides we had other things on our mind, namely how good our squad was shaping up for the upcoming 1970-1971 HAAL season.

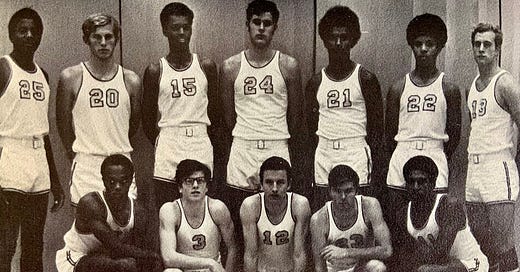

We had talent in the starting lineup, talent coming off the bench. Dave Falkowski was our point guard, a clever and quick little guy who drove taller guards nuts when they tried to dribble against him. He took the ball away from them as cleanly as a pickpocket lifting a passenger’s wallet on a crowded commuter train. Dave lived on Minnie Street same as me and around the corner from him was our center, a six-foot-six force in the middle, Jim Langenstein. Big Jim transferred out of St. Elizabeth’s, a private Catholic high school in Oakland and a perennial East Bay basketball power, because he wanted to play with the kids he grew up with. That included Craig Fry, a talented jump shooter who was automatic from the free throw line. He, Jim, and Dave were all juniors.

Our power forwards were seniors, each around 6-feet-four inches tall. Rebounding specialist Frank Volasgis could body up under the boards when getting physical was required. Joe Rucker transferred over from another Bay Area prep basketball power, Castlemont High in Oakland. Joe was a scorer and a leaper, skinny and long-limbed with the easy grace of a dancer. He and Frank both sported puffy Afros. Those five plus Number 12 and me comprised our seven-man core.

Making sure we all came together as a unit was Coach Fuccy, who was young and passionate with three beautiful daughters and a beautiful wife. He taught at Hayward High and had played basketball himself for the school in his prep days. His position then was guard and the years had not diminished his talents from the outside. Challenge him to a long-range shooting contest after practice and he’d beat you every time. We identified with him because he wanted to win as badly as we did.

First on the schedule was a preseason contest: Bellarmine High School of San Jose, yet another private Catholic institution with a blockbuster athletic tradition. It was an away game, at their gym. It promised to be a stern test for the public school boys of Hayward.

Here is Part Two of “The Public School Boys of Hayward:” ‘HHS to the TOC!’ Underdog Farmers Take on the World.’

And here is Part 3: A Burden Shared is a Burden Lifted

Many Hayward and East Bay people read and enjoy Tilting West (formerly “Favorite Things.”) If that describes you and you like this content, please share it with friends and encourage them to subscribe. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. The only way to have good music, movies, art, entertainment, and writing in your life is to support the people who create it.