A Burden Shared is a Burden Lifted

The third and final part of The Public School Boys of Hayward: A Story of Joy, Heartbreak, and Healing

Writing this series has been a real learning experience for me. Here are two things I’ve learned: 1) How universal the experience of high school is. Even people who have never lived in Hayward, or who grew up in a different time than I did, have responded to it because it reminds them of their high school days. And 2) How if you open up and share vulnerabilities, people tend to listen, support, and even share their own. That is, in essence, the theme of this final chapter in the story.

If you missed the first two installments, here is Chapter One: The Public School Boys of Hayward. And Chapter Two: ‘HHS to the TOC!’ Underdog Farmers Take On the World. Please enjoy! As always, if you like what you see here, be sure to subscribe and share it with friends. Thank you.—Kevin

There were less than two minutes left to play, and the game was on the line. The Kansas City Chiefs led the Buffalo Bills, 27 to 24, in the AFC Divisional Playoffs last January in Orchard Park, New York, home of the Bills.

Buffalo’s 26-year-old placekicker, Tyler Bass, lined up to take the 44-yard field goal attempt that if successful, would tie the game. The ball was snapped. The holder placed it down. Bass put everything he had into it.

He missed it. The ball sailed wide right. Buffalo had lost the game and its opportunity to advance in the playoffs.

You don’t have to be a professional athlete to know how Tyler Bass must have felt at that moment. Anyone who has played youth sports—boys or girls, at virtually any age—knows how intense the pressures to perform are. And how deeply disappointing it can be when things don’t go your way. You try out for the high school team and get cut. Or you’re on the team but mainly you sit on the bench because the coach won’t play you.

As they console a child or grandchild who has collapsed into tears after making a bad play or suffering a hard loss, parents and grandparents understand these pressures too. The feelings can go very deep and linger a long time because you can’t undo what’s been done. The game is over but the hurt remains.

Bass is a well-paid pro athlete who has achieved enormous success in his athletic career and will, we assume, go on to more success in the years ahead. Even so, he will always remember that moment. It’s just the way it goes, in sports and other areas of life. You tend to minimize or even forget the good things you do. The bad things, though, they follow you around.

####

So it is for me when I look back on my senior year at Hayward High when I played on the varsity basketball team. We achieved many marvelous things that season. An overall record of 23 wins and 3 losses, ranked sixth in California, champions of our league. I dated a cheerleader and had kick-ass good fun all season long playing with my six Black brothers and five white brothers who made me better every time I stepped on the court with them.

But then my mind drifts back to a single play that occurred in the title game of the Tournament of Champions, the ultimate prep Northern California basketball tournament of its time, held at the Oakland Coliseum Arena with nearly 10,000 people in attendance.

Our opponent is Berkeley High. Berkeley leads, 64 to 62. Time has almost run out in the fourth quarter. There are 16 seconds left to play.

We have the ball and the chance to tie the game and send it into overtime. Dave Falkowski is my teammate, a guy I grew up with, and a guard like me. We have the ball on our side of the court near the half court line. Dave takes it out and bounces it into me. I turn and start up the court.

It’s fascinating how memory works. As impactful as that moment was, I can remember virtually nothing about it. That is where my mind goes blank.

Something happened. I stumbled or something. Somehow I dropped the ball. That’s all I recall. It’s like when a person is in a car crash and his mind goes dark to shield him from the experience.

My brother Dave Nelson was at the game; he saw those last 16 seconds unfold. After reading the first two parts of this series he called me to ask if I wanted to know what actually happened. I wasn’t sure I did at first but I quickly changed my mind. Fifty years after the event, let’s finally hear the truth of it.

“This is what actually happened,” he said. “Mighty Mouse [Dave Falkowski’s childhood nickname in the neighborhood we all grew up in] took the ball out and gave it to you. You dribbled up court. Everything was fine. You were looking to pass to either Donnie or Jim.”

Yeah, that’s right, I interjected. Donnie Schroer and Jim Langenstein, our two All-TOC stars who had carried us throughout the game. Get them the ball and give them the chance to score and tie the game for us.

Dave resumed, “I think Donnie was cutting across the top of the key looking to get the ball. You were so focused on him that you weren’t aware of a Berkeley guy coming up on you. As you were about to make the pass you could see he was going to block it. You tried to pull back your pass and that’s when it came loose and bounced into the hands of the Berkeley player. He was completely surprised.”

The name of the Berkeley player, I found out while researching this piece, is John Barnes. Surprised but very grateful, he raced down the court and scored. We fell into total disarray after that. We lost the ball, fouled, and Berkeley sunk the two free throws. Final score: Berkeley 70, Hayward 64.

Hearing this story from my brother was like discovering a missing piece of my childhood. Afterwards I never talked much about that game. I’d reminisce about the season but not the way it ended. It was a thing that happened a long time ago, when I was seventeen, and it was over. But it really wasn’t. I still had unresolved questions. And so, late last year, I sought out someone who might have the answers.

####

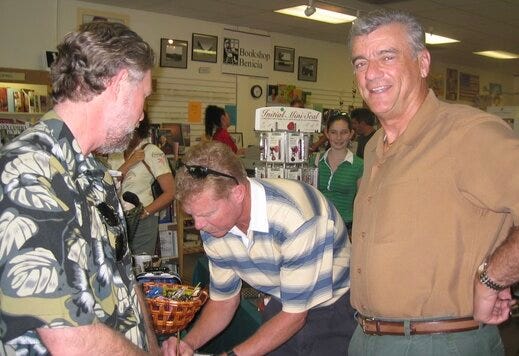

Joe Fuccy and I were sitting in the living room of his comfortable Brentwood home where he lives with his wife, Marti. Brentwood is a fast-growing suburban outpost in the dry and hot eastern flatlands of Contra Costa County. He and Marti moved there some years ago to be closer to children and grandchildren. They have been married 60 years. In the living room and all around the house are framed photographs of their large family. From their backyard you can see vineyards and brown rolling grasslands and in the distance, the bulky mass of Mount Diablo.

It was fall 2023. After lunch at a clubhouse restaurant we returned to his house to sit and talk and catch up a little bit more on things. We’ve been friends a long time. We’ve known each other since my junior year at Hayward—my first on the varsity and his first as varsity coach. He taught and coached at the school for ten years before retiring from teaching to become a financial planner. He and Marti have attended several of my book parties, and they even hosted one at their house in Pleasanton where they lived before moving to Brentwood. I’ve also been to player reunions of his old basketball teams that he has organized.

But in all that time, over all those get-togethers, we had never really talked about the last seconds of the Berkeley game. Finally, I decided to bring it out into the open.

“You know,” I said, “I’ve always felt bad about what happened at the TOC. I’ve always felt like I cost us the championship.”

Joe did not respond at first. He was thoughtful. He seemed to sense the depth of the emotions underlying what I was saying.

“I think you can lay that burden down,” he said. “A lot of things happened in that game. That was only one of the things. It just happened at the very end, that’s all.”

It has occurred to me that the emotions I carry about that game may not just be about basketball. They are surely wrapped up in feelings I have about other losses that occurred to my family and me in those years. Even so, that loss cut deep.

“Thanks, I appreciate that,” I said, adding, “There’s something else about that game I’ve wondered about for a long time. It’s about Donnie.”

Donnie Schroer was my best friend on the team. We broke in as freshmen on the frosh-soph squad coached by Jim Bisenius and played all four years together. He was the star in our senior year, our leading scorer, a marvel at driving to the hoop, hanging in the air, and laying the ball up over the outstretched arms of the defenders. He was down on our end of the floor when I started forward. As my brother remembers, he was who I was trying to pass to when the ball slipped away.

After the TOC we stayed close. He was a waiter and busboy at an Italian restaurant in Hayward, Banchero’s (now closed), and on his recommendation I got a job there briefly as a dishwasher. We still cruised around nights in his Volkswagen usually ending up at Quarter Pound for burgers and shakes. Going out to Bay Meadows remained a favorite pastime of ours, sneaking in, playing the ponies.

After the summer of our senior year I went off to college and we gradually lost touch. Every now and then we’d check in with each other by phone. The last time we talked, he called me. It had been decades since the TOC but that game and my part in it was practically the first thing he mentioned after “Hello.” It pissed me off. You’re kidding me, right? Again? He apologized and we moved on from there.

Based on that call, and well before that really, it was clear how much that loss disappointed him and how much it still weighed on his mind. It was a dream come true to play in the TOC, and my understanding is he never played much competitive basketball after that. Those who knew him and cared about him were also aware of his love for gambling, and the challenges in his life that had followed.

I continued, “It’s probably just me but sometimes I think, you know, what would have happened if I hadn’t dropped that ball. He never got a chance to finish his dreams. That can’t be good, right?”

Joe thought about this, too. He was also a friend of Donnie’s. They had talked many times. “No, I think you can let that one go too,” he said finally. “It was just one basketball game. Donnie is Donnie.”

Then Coach Fuccy surprised me by telling a story—a story that, I realized, he was telling me in order to lift my spirits, console me.

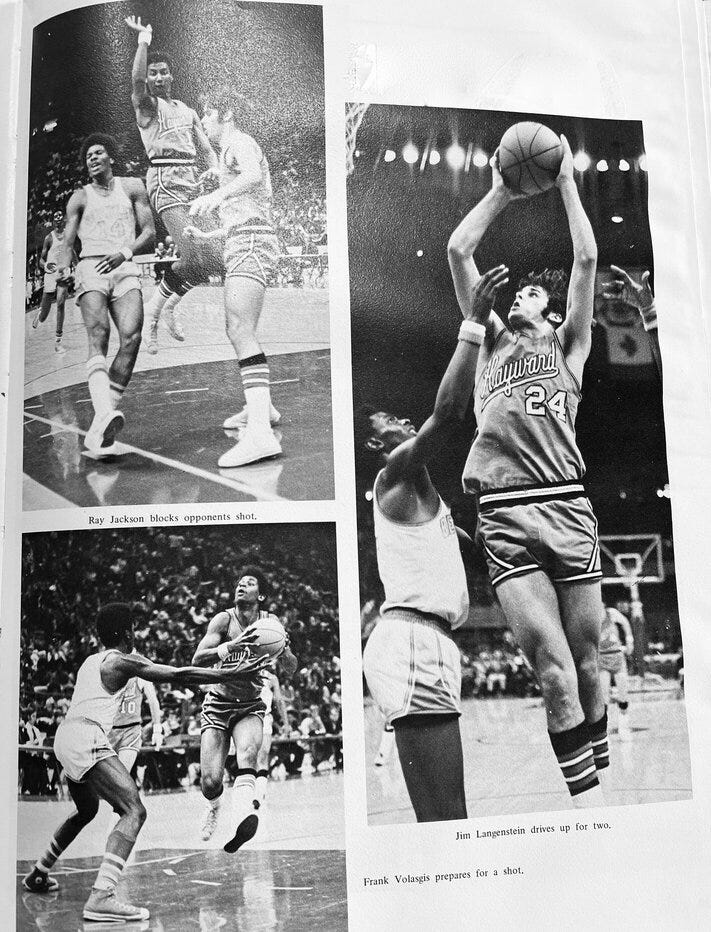

It was about the Farmers of 1972, the year after us. They too were a talent-packed group, featuring four returnees from our squad: Langenstein, Falkowski, Craig Fry, and Frank Volasgis, now seniors. Joining them was a top-flight group up from the junior varsity coached by Charley Kendall that had gone undefeated in league the year before. These included Danny Bell, John Guzman, Mike Engeldinger, Scott Paulson. The gifted Ray Jackson earned a spot in the starting lineup as a sophomore.

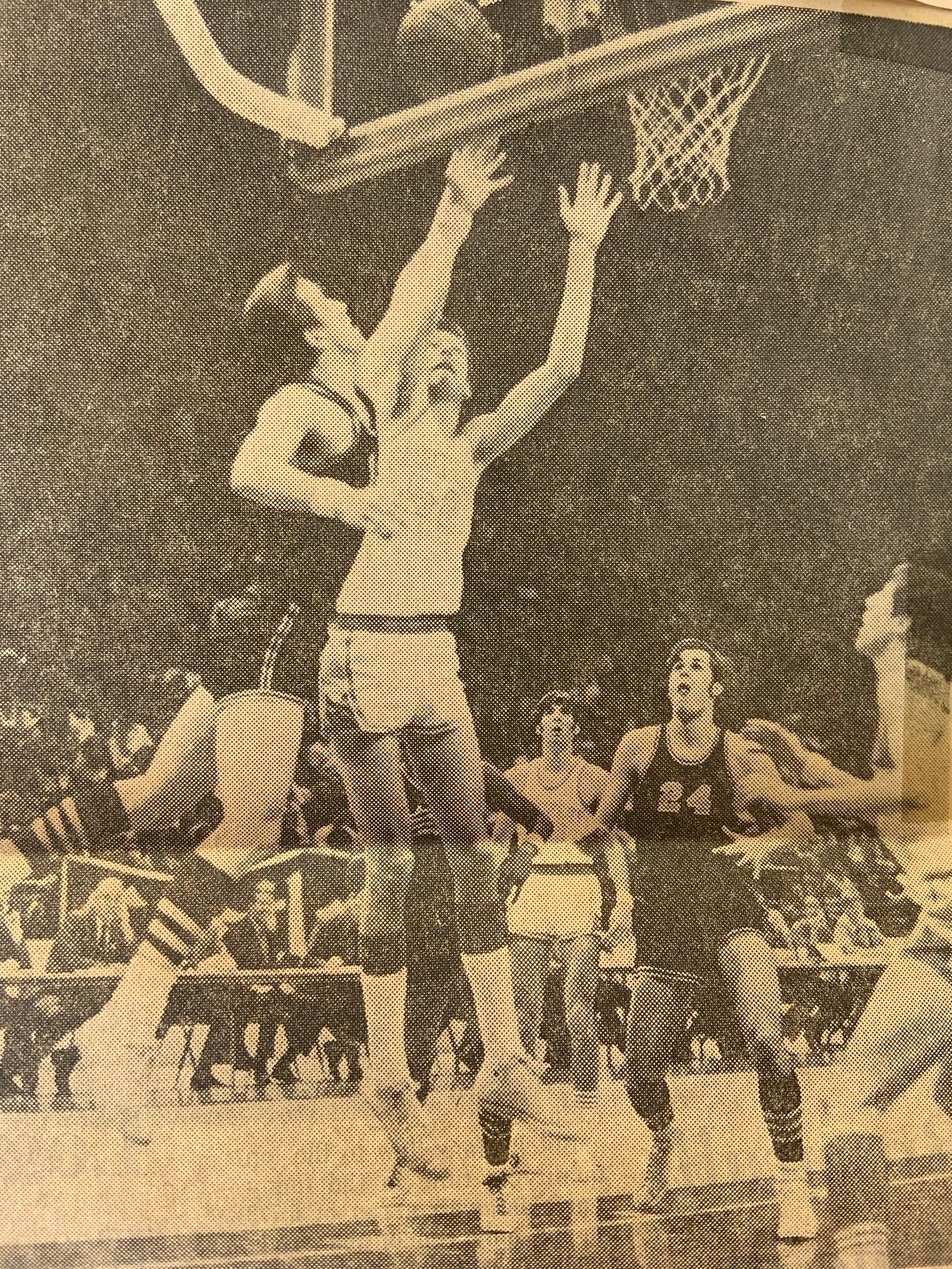

After sputtering through the preseason, that team kicked it into gear during league and went 16-0, winning the HAAL title and earning a berth in the TOC. It took the opening game of the tourney in a squeaker and scored a measure of revenge in the second round by beating Berkeley in another tight contest. For the second year in a row Hayward had reached the finals, and for the second straight year it was facing a massive favorite to win it all: San Joaquin Memorial High of Fresno. Similar to our year as well, a majestic talent stood between them and victory: 6-foot-9 inch Cliff Pondexter. The center-forward could jump through the roof and would later be drafted in the first round of the 1974 NBA Draft by the Chicago Bulls.

I called Mike Engeldinger, who was a guard on that year’s team, to hear what he had to say about playing against Pondexter. “The dude was like a man,” he recalled. “I remember like the first five shots we took against him. He goal-tended all of them.”

San Joaquin Memorial’s strategy with Pondexter was similar to Berkeley’s the previous year with its center John Lambert: Get the ball to the big guy and let him work inside. This caused major problems for the Farmers but after getting down early they came back strong and had cut the lead with about six minutes left to play. The ball went down to Pondexter in the paint. He turned and shot and Jim Langenstein, Hayward’s center, sent it back the other way. “I do remember Langenstein blocking his shot,” said Engeldinger. “Everyone was in awe of that.”

Also in awe perhaps, but knowing how to respond to a loose ball, Falkowski grabbed it and set off at high speed down the court. Suddenly it was a David versus Goliath scenario, with Goliath sprinting after the little guy to catch up with him. The two met at the basket with Falkowski going up for the lay-up and Pondexter swatting it away. In the opinion of many, however, certainly on the Hayward side, there was no doubt about it: goal-tending.

No call, though. No whistles sounded.

Coach Fuccy was on his feet and furious, and the referee slapped him with a technical foul. San Joaquin Memorial converted the free throw, got the ball back and scored, and suddenly Hayward’s momentum had stalled. Pondexter and his mates regained control and once again the public school boys of Hayward came away losers in the TOC title game.

“We were getting after them pretty good with our press,” Joe remembered. “Then that happened and I feel like it cost us the chance to win the game. After I retired from coaching I’d go back to games at Hayward and I’d see people who were at the Coliseum that night. They’d bring it up. They’d make jokes about it.”

Although nobody was being mean, it was not really a joking matter for him. Decades later he still feels the sting. “It makes me feel bad when I talk about it,” he said.

So there it was. Hard-earned wisdom from the coach. In sports maybe, but certainly in life, we’ve all got stuff we’re working on. And some of that stuff hurts pretty bad. We carry those hurts around as if they’re private and ours alone and that nobody else could possibly understand. But everyone does. Because everyone else has hurts the same as all of us.

When I started thinking about writing this piece I called Manny Silva because I knew that one of my subjects was going to be our mutual friend Donnie Schroer. Like me, Manny hasn’t seen or talked to him in a long while and would love to get back in touch with him. So would I. If you see this article, brother, hit me up, man. You have my number and if not, try me at kevinnelson@substack.com. I’ll reply, believe me.

Manny became a police officer (he’s now retired) at the age of 21. When he was going to the police academy learning how to be a cop, every night after class he’d go over to see Donnie at his house. Although Donnie ended up at Hayward and Manny went to Sunset High and played on the team there, the two lived near each other when they were growing up and hung out a lot together.

On the wall of Donnie’s bedroom was a framed photograph of him from the TOC. Manny saw it every time he went over there and still remembers it. Donnie is driving against Berkeley’s 6-foot-11 inch John Lambert. Creative as always, he is spinning the ball up against the backboard with his left hand. The future No. 1 pick of the Cleveland Cavaliers is reaching up to block his shot. Schroer is a foot shorter than he is, and yet Donnie is higher up off the floor. That boy sure could jump.

Epilogue: Death Claims Donnie Schroer