This is a beautiful story, about a son’s love for his mother and their last days together.

It is written by Mark Chester, a friend of mine and longtime journalist colleague. Mark is a professional photographer and writer whose work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, and more.

Photographs of his are in the permanent collections of museums around the country. His books include The Bay State: A Multicultural Landscape, Photographs of New Americans and Dateline America with Charles Kuralt.

Readers may remember our feature on him and his newest book, Roadshow Anthropology, in a previous issue of Tilting West. He and I met many years ago in San Francisco but Mark now lives in Cape Cod where he writes a monthly column for Enterprise Newspapers of Massachusetts. The column contains three brief introductory sections about his photography and techniques.

The personal story begins with “And One More Thing.” “Writing it was cathartic,” Mark confesses, “and a means of dealing with the loss.” Anyone who has ever dealt with the passing of an aging parent or loved one will surely relate to his experience.—Kevin Nelson

By Mark Chester

Why I took the photos

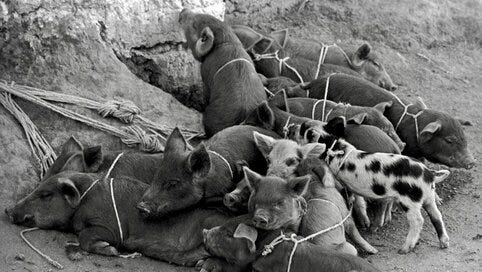

The pigs huddled together displayed lovingness and safety in numbers.

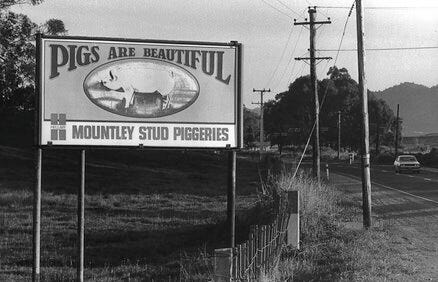

The billboard touting that pigs are beautiful struck a silliness.

How I took the photos

I used a manual Nikon F camera and 28mm wide-angle lens with Tri-X b/w film to include the sows and piglets.

I used a manual Nikon F camera and 135mm telephoto lens with Tri-X b/w film capturing the billboard.

What I like about the photos

I liked that these pigs found their own personality space and comfort zone.

I like the description that pigs can be thought of as being beautiful.

And One More Thing

If only my mother would have listened to her husband, an orthopedic surgeon, perhaps she’d be with us, still kicking up a storm at 102 and commandeering the universe.

Her husband Maxwell for years advised a heart-valve replacement to improve her blood flow, reduce symptoms of heart valve disease and most importantly, prolong life. He repeatedly explained that with the advancement of medical technology, heart valve replacement surgery is not as risky as in earlier days. Her heart had taken its toll over the years that they were married. She had suffered from rheumatic fever as a child.

A news broadcast on CNN reported that “more people need transplants than there are organ donors. Pigs might be a solution. One methodology is xenotransplantation, that is, transplanting a valve from an animal such as a pig or a cow; though a human donor or an artificial one, made of carbon coated plastic, is also common.”

But she would not listen to any of it. Besides, she would be repulsed to be walking around with a pig’s heart or anybody else’s. It was too creepy and unfathomable—and not kosher, though irrelevant, as she was not a religious Jew.

My mother was not the demur, silent, say-nothing type of person. She was authentic, generous, kind, and ready to help anyone in need, always thinking of the other person first. And she was pigheaded as can be. But everyone let it slip because she was Sylvia. She was averse to taking medical advice, relying more on her new-found faith and gut feelings in calling the shots.

She was independent, and a survivor, becoming a widow at eighty-one when her 95-year- old husband passed of renal failure. She had a support group and tons of friends who cared for her in Florida.

I hate Florida!

But when her caregiver called to tell me the news of her stroke, I hurried to the Sunshine State with a ray of optimism.

I had relocated to Cape Cod from California to be nearer at least by plane—just in case. Well, that “case” happened, a year after I had moved to Massachusetts. I arrived at the hospital the next morning. She greeted me with her trademark smile. Her cardiologist was there. He adored her as much as everyone. He told me that she had the biggest heart of anyone he ever knew, with no pun intended; that calmed me and lessened my anxiety.

An only child, I felt even more alone seeing her with tubes going in and coming out from every direction. She managed to sit up.

Diagnosed with aphasia, the loss of ability to understand or express speech, caused by brain damage, she was otherwise physically in good shape, able to move her arms, legs, and hold a glass. The first test for a stroke patient is to determine if he or she can swallow to eat and drink; otherwise a feeding tube is necessary. She passed that round with flying colors.

The next was to assess her mobility, the nurse was explaining a rehab program. Just then the physical therapist arrived to walk her down the corridor. My mother was reluctant, waving her hands as a negative sign. I thought it best to leave them to decide her next step, feeling she was in good hands. My mother was instantaneously well-liked when anyone met her… even when she could talk!

There was a courtyard off the first floor by the cafeteria, where I headed to escape the hospital atmosphere. The stairway was by the visitor’s reception area down from her room. But an inner voice steered me instead to the waiting area close to her room. I had just signed the requisite DNR papers— Do Not Resuscitate—meaning that in my absence, the hospital had authority not to keep her alive on any life support means.

In the waiting room, I couldn’t sit and relax. I began pacing like a caged animal. An inner voice talked to me. Instinctively, I ran back to her room. I saw her collapse in the therapist’s arms. The monitor at the nurse’s station showed no vital signs working.

The station nurse asked, “What do you want me to do ?” Without hesitation or thinking, I blurted, “Bring her back!”

The nurse without missing a beat yelled “Code Blue.” From out of nowhere paramedics appeared to carry my limp mother back to the room. One administered the defibrillator, the other attached a ventilator then placed her on a gurney to wheel her to the cardiac care unit.

I followed Dr. Onstad, the cardiologist, there, my heart thumping louder than my footsteps. Her eyes were closed. The ventilator covered much of her face. We leaned over the bedrails in silence. Trying to compose myself to ask the inevitable question, which he interpreted from my eyes welling up, he said, “Let’s see if she can breathe without the ventilator.”

We both knew that she did not want any heroic measures to keep her alive. As he unhooked the air tubes with his Popeye-like hands, tears poured down my face. He listened with his stethoscope. He smiled. My eyes met his. He gave a thumbs up. She was alive, though unconscious, and breathing on her own.

My legs grew stiff, my body numb. I kept thinking what if I hadn’t been there to tell the nurse to keep her alive?

The next day Dr. Onstad moved her to a remote hospital wing, “the one” where patients just stay in a room and wait in limbo. There was nothing else the cardiologist could do. It was just a matter of time. Her initial stroke, then a heart attack left her vulnerable. Hospice care was the last resort, which the cardiologist authorized.

I met with the Hospice Director at my mother’s condo, signed the mass of paperwork, answered the interview questions, and ordered a hospital bed. Once the hospital discharge was completed, the ambulance brought her home. She looked great, smiling up a storm, though still unable to speak. But she was aware of her surroundings, knowing she was back home.

My mother’s life was now my life—to let her live her final days or months with comfort and dignity.

Hospice of Fort Lauderdale assigned three nurses in eight-hour shifts. All were Jamaican. They liked my mother immediately—no surprise there. Each had her own personality, sensitivity, competence, and lovingness. The three women—and Mom—shared their born-again Christian beliefs.

I stayed on the couch for the next three weeks getting to know them well, and liking them just as much as my mother had. These three “wise women” were my saviors as well, giving me comfort; they felt my emotions. I grew attached and somewhat dependent on each nurse who shared their understanding about life and death.

I observed that each nurse’s shift—morning, afternoon, night—correlated with her own personality. That is, the morning nurse was an administrator/organizer type; the afternoon one was like the school mom who served milk and cookies and the evening meal, attended to hygiene and bedtime needs; and the late-night nurse was the philosopher-introspective type who read the Bible to my mother, combed her hair, and chatted in soft tones with her.

I asked each how they came to be a hospice nurse. Separately, each told me, “Hospice chooses you.”

The three were a personal godsend. They were there to usher in my mother’s journey to her world beyond on August 16, 2003. They gave me closure. They were my inner voice.

To see more of Mark’s writing and his photography, please visit Mark Chester Photography.

A very relatable story by Mark Chester. Losing a parent, being there with them when they are leaving us, it a loving task.

Beautiful piece from Mark; so lovely to have given his Mom that much-appreciated difficult gift.