Mixing the Mob with Pop Art at Vegas Museum

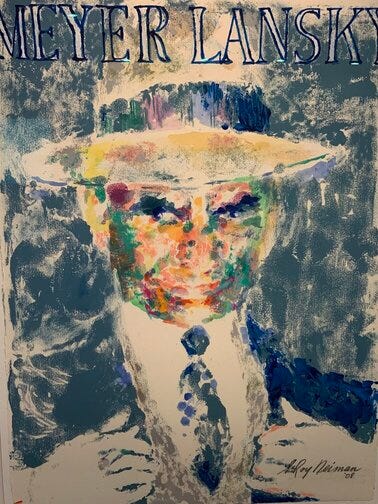

Mafia gangsters always intrigued LeRoy Nieman, who made colorful portraits of them.

There are not many places in the world where you can spend an enjoyable hour or two learning about the exploits of low-life thugs who murdered people and were often murdered themselves for their violent and illegal activities.

But hey, that’s Las Vegas and that’s the Mob Museum. And after you’ve had your fill of all this murder and mayhem, you can head down to the Underground Bar and Distillery and have a drink.

The Mob Museum is located in downtown Vegas in a converted federal courthouse that was once used for arraignments and trials of the very same Mafia figures you’re learning about.

Its three floors of exhibits, photos, and videos tell the story of organized crime in America and law enforcement’s efforts to stop it. It focuses mainly on the old school gangsters of yesteryear but also touches on the international drug cartels of today.

One fascinating room in the museum is devoted to the work of pop artist LeRoy Nieman, who was so intrigued by these lovably loathsome characters that he painted portraits of them.

“I’ve always been magnetically attracted to these guys,” said Nieman, who died a dozen years ago. “Casino czars, political powerhouses, show biz divas, Wall Street whizzes, ruthless impresarios, mob bosses, Hollywood hustlers, mega-buck gamblers—in short, bigwigs.”

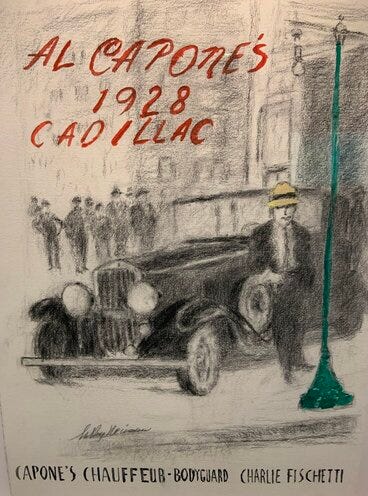

The biggest of the mob bigwigs painted by Nieman was Al Capone.

Capone ran mob operations in Chicago in the 1920s. He and his cronies made a fortune bootlegging during Prohibition and conducting a variety of other illegal rackets. The feds eventually nabbed him for tax evasion.

The actor Edward G. Robinson, who became famous for playing crooks like Capone in the movies, saw this painting of Nieman’s and warned him “not to cozy up to these gangster guys.”

Too late. Nieman came to know the Chicago underworld scene so well that he not only could sketch Capone’s Cadillac, he could also tell you the name of his chauffeur and bodyguard.

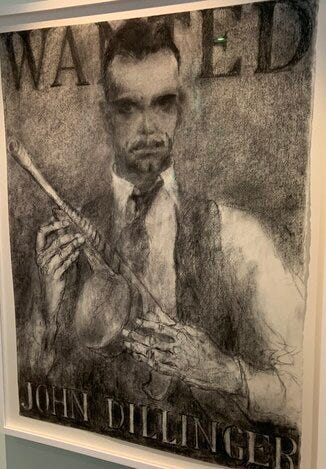

John Dillinger was a bank robber and cold-blooded killer who became the most famous criminal in Depression-era America. In June 1934 the FBI gifted him a dubious piece of immortality—naming him the country’s first ever Public Enemy One.

One month later Dillinger walked out of a Clark Gable movie in his home state of Indiana with two women on his arms—one his girlfriend, the other an informant. She was working confidentially with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to advise him on the whereabouts of the Most Wanted Man.

The FBI was waiting for him outside the theater. A hail of gunfire greeted him. Two bullets to the body and his Bonnie and Clyde-style crime spree was over.

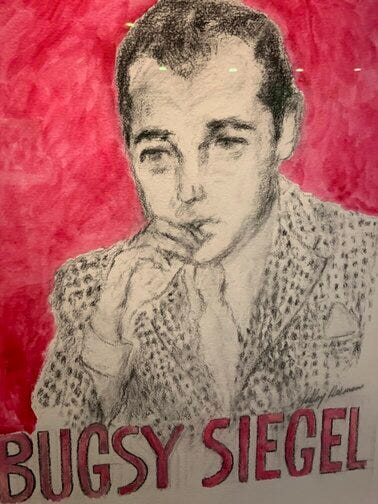

Another violent man who died violently was Bugsy Siegel, a hotheaded member of New York City’s Murderers Inc. Suave and dapper, he came west to help establish the Mafia’s foothold in Nevada, where gambling and prostitution were legal. He also got into bed with Hollywood. His romance with the glitz and glitter of the movies ultimately did him in.

On June 20, 1947, his one-time brothers in Murderers Inc. ordered a hit on him at the Beverly Hills mansion of his girlfriend, actress Virginia Hill. A spray of .30 caliber bullets shattered the living room window and Bugsy himself, including two to the head.

There are many theories as to who ordered the hit on Bugsy, and why. Some say Siegel’s operation of the Flamingo Casino in Vegas ticked off Meyer Lansky, and one thing that you did not want to do in those days was make the revenge-minded mob kingpin mad.

Lansky is widely regarded as the inspiration for the Hyman Roth character (played by Lee Strasberg) in The Godfather Part II. He is also famous for saying, “We’re bigger than U.S. Steel,” referring to the size of organized crime in its heyday.

Meyer ran the organized crime syndicate of Jews and Italians that formed the Mafia. After the feds eventually caught up with him he fled to Israel in the 1970s to avoid prosecution. But the Jewish state refused him entry, and when Lansky set foot back on American soil at Miami International Airport, the FBI greeted him with handcuffs. He died a broke and broken man.

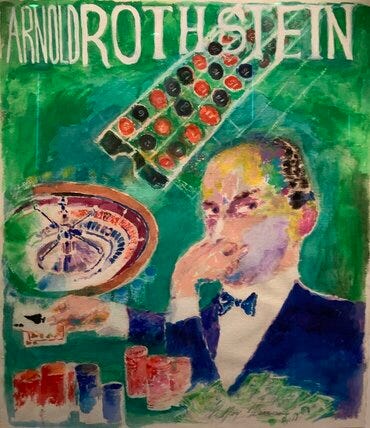

My favorite mobster: Arnold Rothstein. I wrote about him in The Golden Game: The Story of California Baseball (Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press). Now why would a Chicago gambler and bootlegger enter into a history of California baseball?

Well, Rothstein’s most famous gambit was engineering the 1919 Black Sox Scandal. During the World Series that year members of the Chicago White Sox allegedly took money from gamblers to throw games and lose the Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Several of the Black Sox who were supposedly on the take, such as Hal Chase and Chick Gandil, had California ties.

The Great Gatsby briefly features a character, Meyer Wolfsheim, who was based on Rothstein. In it F. Scott Fitzgerald describes him as “the man who fixed the World Series back in 1919.” Which is the perfect segue for Monday’s piece in Tilting West: a look at the Underground bar with its speakeasy theme and photos of Jazz Age personalities such as Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda. Until then—