When you’re driving you often pass over bridges and stretches of highways named in memory of politicians, law enforcement, and military people. It is not often, though, that you pull off at a highway junction dedicated to a Hollywood superstar who died mere feet from where you are stopped.

And yet here we are, at the James Dean Memorial Junction.

We are east of Paso Robles in a lonely section of inland central California where Highways 46 and 41 meet. It is early on a Saturday morning in June, hot already and certain to get hotter still as the flaming red ball in the east lifts higher in a mostly cloudless sky. We are perched precariously on the shoulder of the road, far enough to be out of the flow of traffic but not far enough to feel safe.

Cars and trucks rocket by us, traveling as fast or faster than what Dean was going in his new 1955 Porsche Spyder when the terrible collision occurred. This is no tourist stop. This is no stop at all. We dare not leave the car for fear of being clipped by a driver roaring past who would never expect to see someone outside on foot there.

A highway construction project is going on at the site, although the tractors and heavy equipment parked nearby are shut down for the weekend. They are rebuilding the James Dean Memorial Junction to bring it up to modern standards, a good thing it would seem. These two state highways were once farm country roads, there were no towns of any size around here. You could drive for an hour and maybe only see a vehicle or two on the road.

This may have been why Dean was driving so fast (besides the fact he loved to drive fast, lived for it). He was out in the boonies, lonely and desolate farm country, nothing and nobody around for miles. It was close to sundown, September 30, 1955. Flying west on Highway 46 with his mechanic buddy in the seat next to him, probably the last thing Dean ever expected to see was another vehicle, a Ford Tucker, having come down Highway 41, turning left onto 46 at the exact same second that gorgeous black beauty of a sports car appeared.

If Dean had arrived there 30 seconds earlier, or 30 seconds later, he would have lived; the accident would have never occurred. In the first scenario the Porsche blows through the junction before the Ford reaches it; in the second scenario, the turning vehicle appears in time for the man behind the wheel, not just some Hollywood pretty boy but a skilled and experienced race car driver, to see it and take defensive action. Dean saw it too late, and in that instant passed from life into legend. The other two men involved, the mechanic and the man in the Ford, were both injured but survived.

I have always been a fan of Dean’s, and I know I’m not alone. A lyric in a recent Taylor Swift song marvels about a man she fancies who “got that James Dean daydream look in your eye.” In their song “Cool” the Jonas Brothers “woke up feelin’ like a new James Dean.” Earlier generations have dug his look and vibe, too. The Eagles devoted an entire song to him in their On The Border album and Don Mclean, in his “American Pie” tribute to another teen idol who died young, Buddy Holly, sung about how the jester sang for the king and queen “in a coat he borrowed from James Dean.”

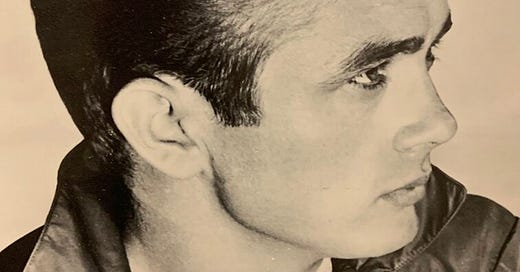

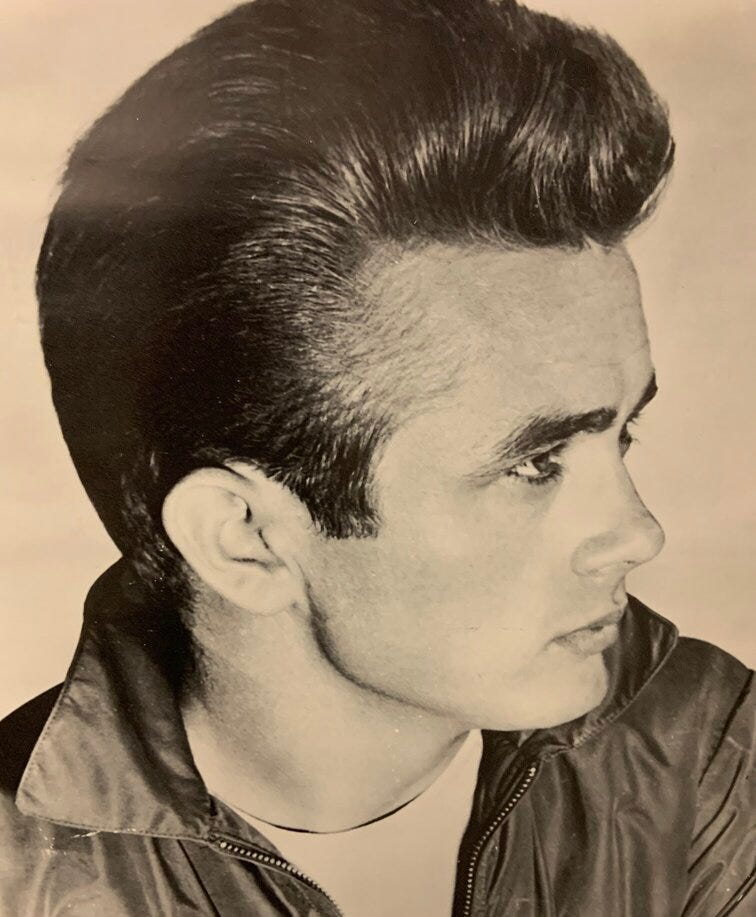

Dude was cool then, dude is cool now. This man who never reached his 25th birthday is perpetually young and still in demand. Decades and decades after his passing—the 70th anniversary will be next year—his estate still earns $5 million a year in licensing his forever hip and rebellious image to advertisers and other firms.

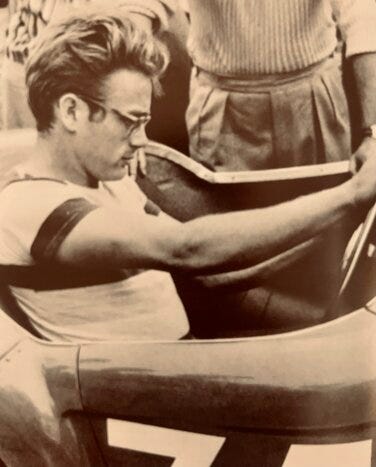

In his all-too-brief career Dean appeared in but three movies: East of Eden, Rebel Without A Cause, and Giant. Only East of Eden, based on the Steinbeck novel, came out during his lifetime. The film was set in the valley where Dean was headed when he was killed; his plan was to participate in a Salinas sports car race the next day. His magnificent performance in that film alone gives a sense of how much the movies lost when they lost him. Rebel, his second film, was rushed into theaters shortly after his death. It became a box office hit and remains a vivid portrait of teen rebellion and angst in 1950s postwar America.

Dean’s acting and on-screen personal magnetism endeared him to audiences around the world, although his star has surely dimmed over time. In the 1980s a wealthy Japanese businessman paid for the construction of a memorial sculpture close to the scene of the crash. Of all nations besides our own, Japan may have loved Dean more than any other. I own a book of Sanford Roth photographs that covers the last three months of his life, including shots of him shirtless washing his beloved Porsche and filming Giant with the radiant and ravishing young Elizabeth Taylor. A Japanese company published it, and all the writing is in Japanese.

The memorial has fallen on hard times, however, it’s now a bit of a mess. You have to turn off busy Highway 46 and go down a frontage road to find it. It is in the parking lot of the Jack Ranch Cafe, which was closed the morning we were there. It may be closed permanently, I wasn’t sure. Two seemingly abandoned vehicles were collecting dirt outside it. Against a nearby fence was a sad little wooden shrine that in its heyday must have been a place where fans left pictures, flowers and other tokens of esteem for their fallen idol. What is there now resembles a little trash dump—some plastic flowers, an empty water bottle, a can, and pieces of broken glass in the dirt.

The sculpture is not in very good shape either. The effects of time—corrosion, bird droppings—have all but completely obscured the words on the dedication plaques at the base of the tree. The oak around which the sculpture stands is called the “Tree of Heaven,” although based on appearances it’s hard to see why it deserves such a lofty name. I would have asked someone about its meaning except that besides my wife, nobody else was around. Nor did it look like anyone had been there for a very long time.

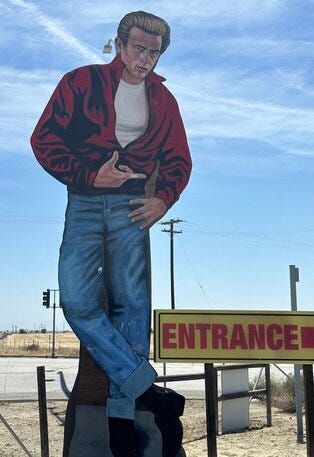

The Tree of Heaven is west of the crash site. Coming from Paso, we stopped there first, made our nerve-wracking pause at the junction, then traveled 25 miles east to the final stop on our tour, Blackwell’s Corner General Store. Blackwell’s is on Highway 46 not far from the junction with Interstate 5 in the Central Valley. It’s a gas station-truck stop and a must-see destination for the thousands who come here every year to see for themselves the place where Dean stopped to buy a pack of cigarettes, his last smokes, before pushing on.

In the fifties Blackwell’s sold Richfield gasoline, today it’s Shell. Outside there are two oversized representations of Dean’s image. One is of his face, garlanded by flowers. The other is of him standing and pointing the way into the entrance of the store. Despite being made of reinforced plywood, he looks as cool as ever with that great hair of his, blue jeans, white tee, and his trademark red jacket with the collar turned up.

The reason I wanted to come to Blackwell’s and these other places was that some years ago I wrote a book, Wheels of Change, a history of automobiles in California that won a writing award. Most any writer will tell you that the best part of the job is the research, and I loved digging into Dean’s happy-sad life. But I had never been to where it had all ended, and because of that something about the project felt unfinished for me.

Here’s an interesting bit of movie lore related to Dean and what came about after his death. The next movie after Giant that he was signed to star in was Somebody Up There Likes Me, a boxing biopic. With Dean out of the picture, the producers cast in the lead role a then-unknown actor who was very much like him: super-talented, drop-dead handsome, with a smoldering stick-it-to-the-man swagger adored by younger audiences..

His name: Paul Newman. Newman’s star turn in Somebody launched his movie career. The next film he starred in, The Left-Handed Gun, in which he played Billy the Kid, had also been developed for Dean.

Inside Blackwell’s there are shelves and shelves of packaged snacks and food items catering to travelers. Cold cases selling soft drinks and beer line one wall. Blackwell’s makes fudge on the premises, and you can get free samples or make a purchase at the “East of Eden Fudge Factory.” Close by is an old Ford jalopy gussied up to look like it just got off the road from Steinbeck’s “Mother Road,” his name for Route 66 which brought migrants from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and other states to California to work on the farms during the Dust Bowl 1930s.

The rear of the store contains a section devoted to Dean’s memory. Mounted in a glass display are supposedly his driving goggles—”Found after 62 years!” says the sign. There are framed newspaper clippings, other mementoes, and as you would expect, lots of photos of him. Strangely, there are few if any pictures of his female co-stars in East of Eden (the lovely young Julie Harris), Rebel Without A Cause (the incandescent Natalie Wood), and Elizabeth Taylor in Giant. Instead there are lots of images of Marilyn Monroe, another beautiful, beloved figure who died too young under sad circumstances.

Leaving Blackwell’s and turning our vehicle towards home, both my wife and I felt glad we had seen what we had seen. It was not the usual tourist thing, more somber and thought-provoking. I kept thinking back to the idea of how important seconds are in our lives and yet what little value we place on them. Sixty seconds in a minute, 3,600 seconds in an hour, 86,400 in a day. Because there are so many of them and they pass by so quickly only to be replaced by another equally insignificant one, we don’t tend to think about them much. But as James Dean would tell you if he could, mere seconds—a turn of the head, if you will—can make the difference between death and life.

t