A Hymn for Franklin D. Roosevelt

On the Anniversary of his Birthday, the Amazing Wartime Story of the Navy Hymn

The delivery had turned dire. Over 24 hours had passed and the baby had not come. The mother was terrified. She had given everything there was to give and still there was more to give. Chloroform, administered by the bedside doctor, relaxed her and finally it happened. She pushed that baby out and out he came—blue and still. Air was puffed into his tiny lungs and when his wails of protest filled the bedroom of the family home in Hyde Park, New York, his exhausted mother burst into joyful tears.

Her name was Sara Delano Roosevelt. The labor and delivery were so hard on her she never had another child. Her son was ten pounds at birth. His name was Franklin, and he grew up to become the 32nd president of the United States and the only one ever elected to four terms in office.

The date was January 30, 1882. This year, the 142nd anniversary of his birth, falls on a Tuesday. As is traditional on this day celebrants will gather for a ceremony in the Rose Garden at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in memory of the man who is warmly remembered as the architect of the New Deal and America’s leader during the turbulence and horror of World War II.

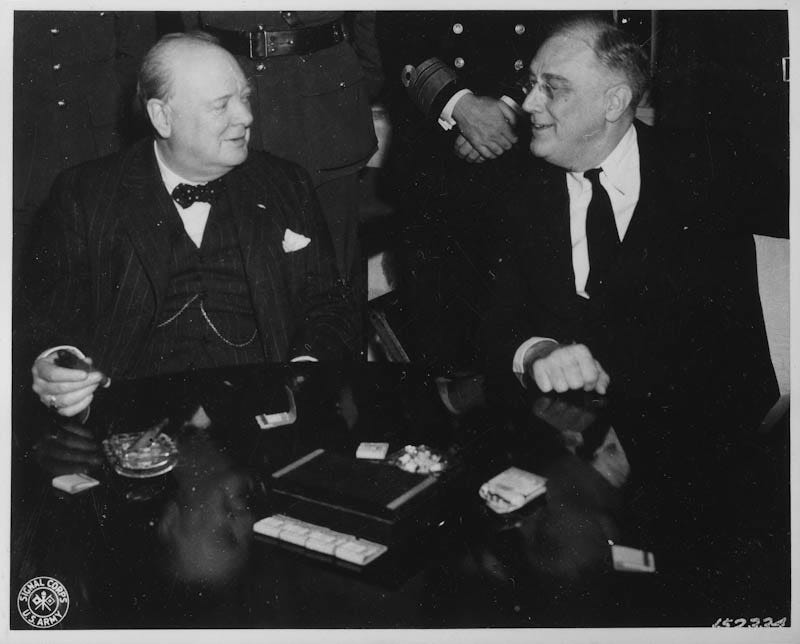

One moment that may be recalled during the ceremony is not nearly as well known as the big events of FDR’s past. Nevertheless it was among the most powerfully emotional days of his presidency. The day was Sunday, August 10, 1941. It took place aboard ship on the waters of Placentia Bay off the southeastern coast of Newfoundland, Canada, where the prime minister of Great Britain and the president of the United States were meeting in secret to discuss the war against Adolf Hitler and the German Reich.

Winston Churchill and his beleaguered yet resolute nation were already fully engaged in the fight. The U.S. was still on the fence, assisting Britain in a variety of ways but had not yet entered the fray. That would change suddenly four months later when Imperial Japan would launch its surprise early morning bombardment of the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

FDR had left Washington days before on the presidential yacht Potomac, moving over to the USS Augusta under the cover of secrecy. Six escort ships armed to the teeth accompanied him to the rendezvous point while the Potomac sailed on as a decoy pretending to take the president on a publicized long-planned fishing trip. Instead he met Churchill as scheduled on Saturday the 9th. First “Winston, good old Winston,” as he was fondly referred to in war-torn Britain, where his eloquent and inspirational radio speeches had rallied the underdog nation against the massive German onslaught, came aboard the Augusta. The two leaders and their staffs and high military command held discussions all day.

The next morning they held church. FDR returned Churchill’s gesture of Saturday and crossed over to the HMS Prince of Wales, the ship that had carried the Englishman and his contingent across the Atlantic. But this “Divine Service,” as it was called, was not just for the top brass. Hundreds of American sailors came aboard too, joining their British enlisted counterparts in a show of unity and shared faith. Years later, writing in his Nobel Prize-winning six-volume account of the Second World War, Churchill would describe this scene as only he could:

“None who took part in it will forget the spectacle presented that sunlit morning on the crowded quarterdeck,” he wrote. “The symbolism of the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes draped side by side on the pulpit; the American and British chaplains sharing in the reading of the prayers; the highest naval, military, and air officers of Britain and the United States grouped in one body behind the President and me; the closely packed ranks of British and American sailors, completely intermingled, sharing the same books and joining fervently together in the prayers and hymns familiar to both.”

Churchill himself chose the hymns that were sung by this most extraordinary congregation. They were: “For Those in Peril on the Sea,” “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” and the final hymn of the service, “O God, Our Help in Ages Past.” “Every word seemed to stir the heart. It was a great hour to live,” he wrote, adding with heartbreaking poignance. “Nearly half those who sang were soon to die.”

I listened multiple times to all three hymns, following along with the lyrics that are available on Spotify or hymnary.org, a kind of IMDB of sacred hymns that I came across in my research. Being the son of a Navy Chief Radio Technician who served on a destroyer in the Pacific during WWII, “For Those in Peril on the Sea” spoke the strongest to me. Another name for it is “Eternal Father, Strong to Save,” the first line of the hymn. But its best known name is also the simplest: the Navy Hymn.

And, as it turns out, it was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s favorite hymn. He knew all those archaic lyrics, he had sung them many times. One can easily picture him and good old Winston raising their voices in stirring concert with those brave young men whose fates were so uncertain.

FDR’s close relationship with the sea-going branch of the service began in 1913 when newly elected president Woodrow Wilson appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy. A state senator from New York, he was a civilian who had never served in the military. Nevertheless he threw himself into the job, advocating for a more aggressive defense build-up before and during World War I, a view that often put him at odds with his more isolationist boss. Early in his tenure as assistant secretary FDR took a tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard where he inspected one of the ships being built there, a ship that was itself doomed to die. It was the USS Arizona.

The Arizona was one of the ships that was sunk at Pearl Harbor under the onslaught of 350 Japanese aircraft, 35 submarines and a flotilla of ships. The attack lasted a total of one hour, fifteen minutes. It killed 2,403 Americans and destroyed or damaged the Arizona, seven other Navy battleships and 11 more ships. The next day Roosevelt, now president of the United States, delivered a nation-stirring radio speech of his own, declaring December 7, 1941 as “a date which will live in infamy.”

Four years later Roosevelt’s favorite hymn, the Navy Hymn, would be played at his funeral in his birthplace and family home at Hyde Park. He did not live long enough to see the Allied victory over Germany and Japan. The hymn he loved was written by two 19th century English clergymen and choirmasters, William Whiting (words) and John Bacchus Dykes (music). It begins with the line “Eternal Father, strong to save,” followed by a heartfelt plea: “O hear us when we cry to thee, for those in peril on the sea.”

Antiquated as they are, the lyrics speak clearly, asking God to take care of all those who risk their lives at sea and bring them safely back home. “From rock and tempest, fire and foe, protect them wheresoe’er they go,” says the last stanza. “Thus evermore they shall rise to Thee, glad hymns of praise from land and sea.”

The Navy Hymn continues to be sung and performed by United States Navy bands and choral groups around the country. It is played at official ceremonies, memorial services at Arlington National Cemetery, and at the funerals of Navy veterans and those who have served the Navy in a civilian capacity. Twenty years after FDR’s passing the nation again mourned the shocking death of an American president. John F. Kennedy was a Naval officer who fought in the South Pacific during World War II. As his body was carried up the steps of the Capitol building to lie in state in the Rotunda, they played the Navy Hymn.

It is a different country than it was in 1963 or 1941. And a different military. Yet for all these changes young people in uniform still risk their lives and face uncertain fates, and they and their loved ones still pray for their safe deliverance home. In commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, hear the Naval Academy Glee Club at Annapolis sing “O Father, Strong to Save” (2:28):